The Bunker Hill Connection - "Don't Fire Until You See The Whites Of Their Eyes"

As the commemoration of the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution continues, a recreation of the Battle of Bunker Hill has been planned for the weekend of June 21 and 22, 2025, (albeit in Gloucester, Massachusetts, twenty-five miles northeast of the actual site, due to the urban nature of Charlestown in the 21st century, its organizers indicate). As is the case with the Battle of Lexington and Concord, there are multiple connection between the events of June 17, 1775, and the Massachusetts militiamen who escorted the Convention Army from Saratoga to Massachusetts in 1777.

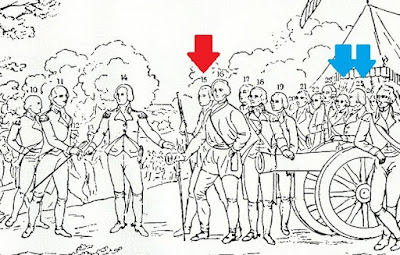

Perhaps the most dramatic of these connections is one of the men associated with the order "Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes." Historian and author J.L. Bell, creator of the Boston 1775 blog, examined the origin of this quote in detail in a June 17, 2020, article in the Journal of the American Revolution. Bell traces the Bunker Hill order story back to 1800, and the Rev. Elijah Parish of Byfield, Massachusetts, who delivered "An Oration, Delivered at Byfield, February 22d, 1800, the Day of National Mourning for the Death of General George Washington." Parish, Bell notes, included a footnote describing the Battle of Bunker Hill, stating that he had learned from a minister in Connecticut that "[Colonel Israel] Putnam was the commanding officer of the party, who went upon the [Bunker] hill the evening before the action: he commanded in the action: he harangued his men as the British first advanced, charged them to reserve their fire, till they were near, ‘till they could see the white of their eyes,’ were his words.” [1]Bell goes on to share later historians questioned who, if anyone, gave such an order at Bunker Hill, and that over time several authors attributed the quote to Colonel William Prescott of Pepperell, Massachusetts (noted above by the red arrow in the key to the figures pictured in John Trumbull's painting, "Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill"). The Boston National Historical Park website's biography of Prescott cautiously notes: "As the British infantry approached, Prescott shouted to his soldiers. The infamous order to 'not fire until you see the whites of their eyes,' is attributed to Prescott in American Revolution lore. While possibly a myth, Prescott likely reminded his militia to not fire at Redcoats too far away." The National Park Service biography briefly references his service after the Siege of Boston, and in a somewhat misleading way, noting simply: "Prescott continued to serve in the Continental Army; he fought around New York City and at Saratoga, NY for the cause of American independence."

David How, who fought at Bunker Hill, served in the Continental Army in 1776, and escorted the British column of the Convention Army from Saratoga to Prospect Hill in 1777, had strong feelings about Prescott. According to a biography of How which accompanied the publication of his diary, "On the day of the battle [of Bunker Hill] he [How] was stationed in the "fort" on the hill, and thus took an active part in the struggle. ... How always gave a large share of the credit due for the glorious work of that day to Colonel PRESCOTT. Many years after that eventful battle, and but a few months before his death, a friend read to him an article from a Boston newspaper, relating to the battle, and asked his opinion of General PUTNAM. How replied that he had "never heard anything against him in the army." He was then asked what he thought of Colonel PRESCOTT. He answered, "Had it not been for Colonel PRESCOTT there would have been no fight." Pretending that he was not quite understood, his friend repeated the question; but the answer was the same. Not yet satisfied, the question was again pressed, when How arose from his chair, and raising his hand, exclaimed, with all the power of voice he could command, - for several years his voice had been scarcely audible, — 'I tell ye, that, if it had not been for Colonel PRESCOTT, there would have been no FIGHT. He was all night and all the morning talking to the soldiers, and moving about with his sword among them in such a way that they all felt like fight'." [2]Although Prescott served as a colonel, commanded a regiment, and was chosen to lead the Provincial forces onto Bunker Hill the night of June 16, 1775, he served as a volunteer during the Saratoga campaign, in Captain James Hosley's company with Colonel Jonathan Reed's Middlesex County militia regiment. [3] While Prescott's role in the Saratoga campaign does not appear to have been anywhere near as prominent as it was at Bunker Hill, his presence earned him a central place in Trumbull's painting "Surrender of General Burgoyne". As indicated by the red arrow on the key above, Trumbull placed Prescott immediately to the right of Major-General Horatio Gates, closer even than brigadier-generals John Glover and William Whipple (marked by blue arrows), who would accompany Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne from Albany to Cambridge, while Prescott presumably marched with the German column.

1777 March Blog Home Overnight Stopping Points Towns and Villages Along the Way

General Whipple's Journal Burgoyne in Albany Annotated Bibliography

[2] How, Diary of David How, ix-x.

[3] Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, 12:753-754.

Comments

Post a Comment