Ensign Thomas Anburey - "A Caution To Others"

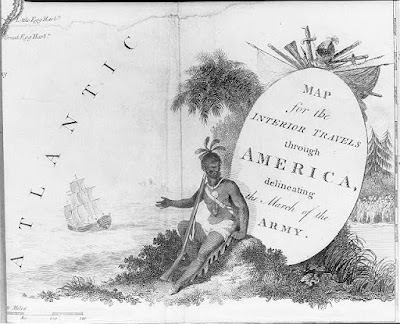

I have used a number primary sources, letters or other documents written by individuals with a direct connection to the march of the Convention Army, to research and write posts for this blog. One of the first I encountered, years ago, was Travels Through the Interior Parts of America, In A Series Of Letters, written "By An Officer". Originally published in London in 1789, it has been reprinted on several occasions and in several languages, including almost two centuries later by the Arno Press, in 1969. While the title page doesn't name the author, the work is dedicated "To Earl of Harrington, Viscount Petersham and Colonel of the 29th Regiment of Foot" by Thomas Anburey. [1]

Anburey shares his story through letters, as the title indicates, written to "My Dear Friend", beginning on August 8, 1776, when he left Cork, Ireland, by ship. Eleven weeks later he writes from Quebec, having arrived in Canada after a "fatiguing passage." What follows is an account of life in Canada and happenings of the war, until on June 14, 1777, he shares that he is "... entering upon the hurry and bustle of an active campaign." [2]

Over the next four months his letters are dated from locations the field during the Saratoga campaign, until on November 10, 1777, he writes from "Cambridge, in New England." He continues his account with his experience in Cambridge, the march of the Convention Army to Virginia in 1778 and his time there, release from captivity in 1781, and his arrival in Falmouth, England, December 15th, where he writes "... this will be the last of our literary correspondence, permit me, before I conclude, to apologize for any inaccuracies of expression, and every little fault that may have occurred." [3]

In the preface to his book, Anburey states he was requested to publish his letters "... as they contained much authentic information, relative to America, little known on this side of the Atlantic..." In Letter XLII, the first in Volume II, he notes what is likely another of his reasons for publishing his work, a defense of the Saratoga campaign and justification for the surrender, warning: "Our melancholy catastrophe will be a caution to others in power, in their directions to a General..." [4]

While British Lieutenant Francis (Lord) Napier and the keeper of the anonymous journal of the 47th Regiment simply listed day by day the places they stopped and the miles they traveled, Anburey shares details. Four letters, XLII, XLV, XLVI and XLVII, cover the surrender at Saratoga and march of the British column of the Convention Army, beginning to end. Included is crossing the Hudson River, the birth of a baby to a soldier's wife in the back of a wagon during a snowstorm, his meeting the captor of a British officer hung as a spy, and the British column's arrival at its barracks at Prospect Hill.

So who was Thomas Anburey, and can he be relied on? Researching the identify of Anburey turned out to be, in his own words, "a caution to others." Vermont historian Ennis Duling labeled him a "fraudulent source" for his description of the July 7, 1777, Battle of Hubbardton. Several aspects of his account troubled Duling: a false surrender by American forces, sniper fire aimed at British officers, Anburey's description of the terrain, and the return of the watch of slain American Colonel Ebenezer Francis to his mother a year later. [5]

Duling was not the first or the last to criticize Anburey. In 1943 American historian Whitfield Bell wrote a detailed article which Duling relied on, noting that at the time the book was published British reviewers accused its author of plagiarism. Among these charges, Anburey was said to have made extensive use of earlier popular travel books for his descriptions of America, and Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne's 1780 A State of the Expedition From Canada for his account of the military action of the campaign. [6]

Duling questions whether there even was a Thomas Anburey. Allegedly he traveled from Ireland to Canada in 1776 as a "volunteer" with the 29th Regiment of Foot, before being commissioned to fill a vacancy resulting from the death of an officer in the 24th Regiment during the Saratoga campaign, Bell noting "Practically nothing more than this is known of the man." [7] Duling notes that a volunteer by the last name of "Hanbury" was commissioned as an ensign on August 10, 1777, and "Tho[ma]s Anbury" (with no "e") appears on the list of officers signing a parole at Cambridge December 13, 1777. [8]

If Anburey (assuming he existed) crafted a narrative to serve his own purpose, he wasn't the first or the last to do so. Any account of history, or the news of today, no matter who the source or what they say, must be evaluated in the context of all of the evidence available. Still, expect to hear more from Anburey - but not just Anburey, as reliance on a single source for information is highly unlikely to reveal the truth. At the least, the author of Travels Through the Interior Parts of America offers insight on the British perception of the people who, until 1776, inhabited what had been a colony of their nation.

Comments

Post a Comment