Burgoyne's Foreign Troops - "With Regularity and Bravery"

On October 22, 1777, Brigadier-General John Glover alerted the Massachusetts Council that the Convention Army was on its way to Boston, including 2,198 "foreign troops". By foreign troops Glover meant Germans, almost half of the total force surrendered at Saratoga. Labeling them as such, Glover avoided designations often used such as "Hessian" or "mercenary", but reaction in Massachusetts was predictable. Massachusetts residents had a dim view of the German troops fighting with the British to start with. Their reaction was hardly new or unique to New England. Indeed, among the grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence in 1776 was that King George III was "... transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous of ages..."

In addition to British troops and Canadian, Provincial and Native forces, Burgoyne had begun his campaign with five German infantry regiments, along with soldiers from dragoon, jaeger, grenadier and artillery units. Four of the infantry regiments are mentioned in accounts of the march. (The fifth infantry regiment, the Brunswick Regiment Prinz Friedrich, substantially avoided capture not through its bravery or tactical acumen, but rather it being assigned to garrison Burgoyne's forward operating base at Ticonderoga and Mount Independence likely due to the poor condition that Major-General Friedrich Riedesel, the commander of Burgoyne's German troops, found the regiment to be in, a topic addressed by historian and blogger Dr. Alex Burns.)

In addition to British troops and Canadian, Provincial and Native forces, Burgoyne had begun his campaign with five German infantry regiments, along with soldiers from dragoon, jaeger, grenadier and artillery units. Four of the infantry regiments are mentioned in accounts of the march. (The fifth infantry regiment, the Brunswick Regiment Prinz Friedrich, substantially avoided capture not through its bravery or tactical acumen, but rather it being assigned to garrison Burgoyne's forward operating base at Ticonderoga and Mount Independence likely due to the poor condition that Major-General Friedrich Riedesel, the commander of Burgoyne's German troops, found the regiment to be in, a topic addressed by historian and blogger Dr. Alex Burns.)

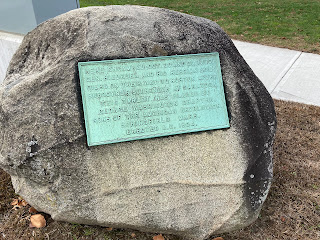

Though many sources refer to the German troops who fought in America during the Revolutionary War as Hessians and mercenaries, only one infantry regiment and an artillery company with Burgoyne was from Hesse-Hanau. A plaque in West Springfield, Massachusetts commemorates the overnight stop on "Oct. 30 and 31, 1777 [of] Gen. Riedesel and his Hessian soldiers on their way to Boston..." While correct in noting Riedesel and many of his troops spent two nights in West Springfield before crossing the Connecticut River, most were Brunswickers. The regiments they fought with were a mix of professional soldiers and conscripts serving in America under treaty arrangements between England and various German principalities. Dr. Burns also addressed the question "Were the Hessians really Mercenaries" in his blog, and dispels many of the myths related to their service.

The letters and journals of German soldiers with the Convention Army reflect an awareness that their presence was not welcome, and they were often viewed with disdain. An earlier blogpost on what the Convention Army looked like, included descriptions of German troops as being "dirty", "sordid", "emaciated", "lumbering" and "miserable looking". In Great Barrington one German officer found the residents rude and spiteful, and so hostile towards them that there was a need to be on guard against blows. Even those residents along the way friendly to them only sold them what they needed at expensive prices, and pretty young women would laugh at them mockingly as they passed - excepting now and then one who would offer an apple. Local inhabitants were curious as they passed though, with whole families coming to take a look at the prisoners, from private to general alike, and "The greater the rank, the longer and more attentively was one looked at." [1]

Several complained that on the march Americans would steal their horses, the first time being as soon as they crossed the Hudson River. [2] Riedesel himself though had proposed taking horses from local inhabitants in July. Writing to Burgoyne, he argued that doing so would not only provide logistical support the army, but be but a minor inconvenience for the local population who primarily relied on oxen to do work on their farms, and with fewer horses it would be harder to spread word of what Burgoyne's forces were doing. What's more, "This little blood would, at least, be a just punishment for their treason and bad conduct towards their king." [3]

Three days after the end of his disastrous Saratoga campaign, Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne took time in Albany, New York, to write two letters to his superiors, one public, one private, summarizing the events leading to the Articles of Convention. His public account of the fighting at Freeman's Farm included praise for the commander of his German troops. "Major-General Riedesel" he wrote "exerted himself to bring up a part of the left wing, and arrived in time to charge the enemy with regularity and bravery." In a second letter deemed private, but published within months of being sent, he suggested it was the presence on German troops that had forced him to surrender when he did, as "Had the force been all British, perhaps the perseverance had been longer..." [4]

When Riedesel and Burgoyne met again along the march in Worcester on November 4th, Riedesel likely didn't know of Burgoyne's second Albany letter, but may have suspected a share of the blame would come his way. By 1780 Riedesel was well aware Burgoyne blamed him for the defeat that became known as the "Battle of Bennington". Having read Burgoyne's published defense of his campaign, A State of the Expedition From Canada, Riedesel felt it necessary to write to Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick and point out that not only was it incorrect to assume that the Saratoga campaign failed because of Bennington, but that while he proposed the raid, Burgoyne finalized the plans and in any event, how could he as a subordinate commander be more responsible than "... HE who commanded the northern army up to the time of the convention, or HE who first planned the campaign of 1777." [5]

Given Burgoyne's public comment on Riedesel, it's little wonder that he, and his wife who had joined him on the campaign and traveled with the German column to Cambridge, were hurt by Burgoyne's private letter suggesting German forces were inferior to English, and to blame for the defeats of the Saratoga campaign - and the Baroness would neither forgive nor forget.

Next week - The Bidwell House, Part I: “Number Won", "Green Woods", "Lowdontown" and "Hushens”

For more on the Convention Army's 1777 march from Saratoga to Boston, see:

1777 March Blog Home Overnight Stopping Points Towns and Villages Along the Way

Comments

Post a Comment