Celebrating The Season - "We Wish'd Them A Merry Crismes"

Was Christmas celebrated in Revolutionary War era North America? The Convention Army spent December 25, 1777, as prisoners in Cambridge and Charlestown, Massachusetts. Life in the barracks on Winter Hill and Prospect Hill was challenging for those who had surrendered at Saratoga, and any of their family members living with them. British Sergeant Roger Lamb, of the 9th Regiment of Foot, recalled of their time there: "It was not infrequent for thirty, or forty persons, men, women and children, to be indiscriminately crowded together in on small, miserable, open hut, their provisions and fire-wood on short allowance, and a scanty portion of straw their bed, their own blankets their only covering..." [1] If the Convention Army celebrated Christmas of 1777 in any way, I haven't found it in what I've read to date.

Christmas was routinely listed in almanacs printed during the Revolutionary War period, even in New England. Samuel Stearns's "The North-American's Almanack" for 1776 lists Christmas on December 25th, along with the Sundays of Advent and the feast days of Saint Stephen (December 26th) and Saint John the Evangelist (December 27th). Nathanael Low's "Astronomical Diary or Almanack" for 1780 likewise notes Advent and Christmas (and that court was being held in Providence, Rhode Island, on December 25th), but replaces Saint Stephen's Day on December 26th with the notation: "Battle of Trenton".

What did occur on Christmas Day during the Revolutionary War was mixed at best for British and German soldiers in North America. A few months before the fighting started, British Lieutenant John Barker of the 4th Regiment of Foot, stationed in Boston, sarcastically noted in his diary for December 24, 1774: "A Soldier of the 10th [Regiment] shot for desertion; the only thing done in remembrance of Christ-Mas day." [3] A year later, on December 25, 1775, when the British army was under siege in Boston, General Sir William Howe ordered: "The Commanding Officers of the Corps to order their Q[uarte]r Masters to attend at the Long Wharft to receive a Butt of Porter for each Corps, which will be sent to ther Quarters for Christmas.". [4]

Brunswick Dragoon Company Surgeon Julius Friedrich Wasmus, captured at the Battle of Bennington in August of 1777, and being held as a prisoner in Brimfield, Massachusetts, made no mention of Christmas in 1777, or any other of the years from 1776 to 1782 covered in his journal. He did note that in Canada on December 31, 1776: "... a thanksgiving was celebrated in the army; for one year ago today, the enemy was beaten in Quebec...". [5]

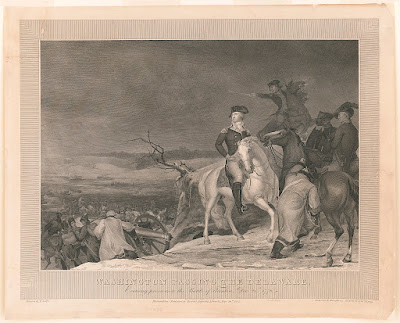

Other German troops fared less well at Christmas in 1776. American forces crossed the Delaware River on the night of December 25th, under the command of Major-General George Washington, pictured in a print in the Library of Congress, made fifty years after the event. Their surprise attack on an outpost at Trenton, New Jersey, the following day resulted over 900 Germans being killed, wounded or captured.

British and German troops still in the fight in 1777 fared little better than the Convention Army on Winter and Prospect Hill. A German soldier in Pennsylvania recorded that on December 13th they were quartered in old empty houses with large rooms, but were cold as there were no stoves to heat them. Nine days later they were sent across the Schuylkill River, and spent the night outside while it was snowing. [6] American forces made things worse still, Colonel John Bull noting that he marched with six regiments of militia towards Germantown, and nearing the enemy's lines on the 24th, he drew up his men and "... Sending them 8 well diracted Cannon Ball... We Wish'd them a Merry Crismes by causing them to Beat to arms and fire their Cannon from the Lines..." [7]

A number of modern accounts relate how German troops in America supposedly celebrated Christmas in 1777. A Lancaster Pennsylvania website makes an unsupported claim that the first Christmas tree in America was set up there, and: "In an interesting twist of irony, this iconic symbol of the holiday spirit was brought to the United States by Hessian mercenaries hired by the British to kill American insurgents during the Revolutionary War. The first Americans to see a Christmas tree were likely the guards at the Hessian prison barracks in Carlisle in 1777."

A Connecticut monument makes a competing claim the first Christmas tree in that state, New England or the "New World", depending on who you ask. A stone marker at the Noden-Reed Museum proclaims Windsor Locks, Connecticut, as the "Site Of The First Decorated Christmas Tree In New England" in 1777. Like the Lancaster tree, this first is linked to a captured German soldier. An online article credits this first to "a Hessian soldier named Hendrick Roddemore", who had been captured at the Battle of Bennington and was being held in Connecticut. The author discloses though, that his sources told him the first printed reference to this claim they had found was in the Hartford Courant, in 1955. [8]

If German prisoners did celebrate Christmas in 1777, they must have been quiet about it. Wasmus noted the family he was staying with marked the day of thanksgiving which Stiles wrote of on December 18th, and that while he didn't join with them in celebrating the American victory at Saratoga, “The dinner was delicious, we liked that”. On December 25, 1777, he made no mention of Christmas, but did note a few rumors regarding the war, that sleigh driving in Massachusetts was not as good as it was in Canada, and that "It is so cold that one gets little sleep in his bed at night." [9]

[1] Lamb, Journal, p. 196.

[2] Stiles, Vol. 2, pp. 237 & 240. Congress declared that December 18, 1777, should be a day of thanksgiving, in recognition of the American victory at Saratoga: https://lccn.loc.gov/2020775003. The verses Stiles preached on speak of Joseph, who though his enemies "sorely grieved him, and shot at him, hated him", had been made strong, and he and his people were blessed by God.

[3] Barker, Lieutenant John, (Dana, Elizabeth Ellery, ed.), The British In Boston, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1924, p. 14.

[4] Stephens, Benjamin Franklin, General Sir William Howe's Orderly Book, Kennikat Press, Port Washington, NY, 1970, pp-178-179. The following day those quartermasters were informed that they would "be answerable for the empty Porter Butts, for which they will be oblig'd to pay, if either lost or destroyed".

[5] Wasmus, p. 37.

[6] Popp's Journal, 1777-1783, p. 8, accessed October 27, 2023 at: https://lccn.loc.gov/02024820.

[7] Verena, Tom, "We Wish'd Them A Merry Cristmes", from the blog "American History and Ancestry", December 11, 2014.

[8] The story, this time for "America's First Christmas Tree", was repeated in 2012. at: https://patch.com/connecticut/ellington-somers/americas-first-christmas-tree-the-connecticut-connection.

[9] Wasmus, pp. 96-97. In addition to Wasmus, the journals of Heath, Hughes, and the British and Germans who recorded the 1777 march of the Convention Army make no mention of celebrating Christmas in 1777, or any other of the years from 1776 to 1782.

For more on the Convention Army's 1777 march from Saratoga to Boston, see:

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment