The Battle of Bennington - "Our Officers Who Were Really Captured"

Bennington Battle Day, August 16th, is a state holiday in Vermont. It commemorates the victory of American militia forces over a mostly German detachment from British Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne's army sent to Bennington, Vermont, to seize badly needed supplies. The Vermont Division of Historic Preservation maintains the 306 foot tall Bennington Battle Monument, erected in 1891, to commemorate the victory.

Despite these strong Vermont connections, the battle was fought in New York. American forces fought under the command of New Hampshire Brigadier-General John Stark, memorialized today in prints, paintings, and sculpture, including in the Crypt of United States Capitol under the Rotunda, as pictured on the website of the Architect of the Capitol. Much of the battlefield is a New York state park, near the Walloomsac River just outside the town of Hoosick. The site is not far from the route the British element of the Convention Army took in October of 1777, from New York through Vermont, into Massachusetts.Despite geography, the battle is commonly referred to as the "Battle of Bennington", rather than the "Battle of Walloomsac", or as diplomatically put in a brochure jointly published by the New York Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation and the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation "The Defense of Bennington".

British Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne summarized the outcome in a letter to Lord George Germaine, dated August 20, 1777: "The loss, as at present appears, amounts to about 400 men, killed and taken in both actions, and twenty-six officers, mostly prisoners..." [1]

The Specht Journal offers more detail: "Aug. 17... We got the news that before he could get support from Lt. Colonel Breymann, Lt. Colonel Baum had yesterday been attacked on all sides by the enemy in his position near Sancoik Mills. After an extremely lively defense but not before the entire ammunition both of the artillery and of the muskets had been fired, he was compelled to surrender unconditionally to the enemy with the remainder of his corps. ... Many of the Savages, Canadians and Provincials, who were with the corps and had been dispersed together with Major Campbell and Captain Charret [Sherwood?], arrived at the camp having made their retreat through the densest woods and the most impassable roads... We learned from them that the fury of the Rebels, some of whom were drunk by the way, had especially focused on the captured Provincials, whom they were said to have treated with all imaginable cruelty..." [2]

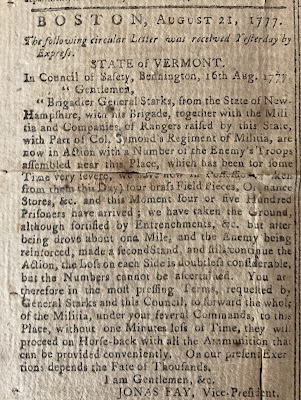

News of the battle reached Boston in days, and was published in the August 21, 1777, edition of the Boston Independent Chronicle and Universal Advertiser. A note from the Council of Safety in Bennington, dated the 16th, shared that American forces had taken four artillery pieces, and four or five hundred prisoners.

One of those taken was Brunswick dragoon company surgeon Julius Friedrich Wasmus. Wasmus' account of his capture notes the confusion that existed when he surrendered. Held first at gunpoint, he was quickly searched and his watch, wallet, knife, notebook, and lighter were taken from him. The American major who took charge of the prisoners was wearing a Brunswick grenadier's helmet, a German ensign's gorget, and a dragoon's saber. [3] The Americans, it appeared, were anxious to take what they could, one noting that on the 16th, "... we retreated back to the main body bringing off all the plunder we could." [4] Burgoyne sought to avoid a similar fate for his men when he surrendered. Among the terms he insisted upon in the Articles of Convention, was Article VI, which stated that none of the prisoners baggage was to be "molested or searched".

The Northern Army took a number of prisoners during the campaign, including up through its final days. Major Henry Dearborn, who commanded the American light-infantry forces, noted captures almost daily at the start of October, before the Battle of Bemis Heights on October 7th, and, in the days leading up to Burgoyne's surrender on October 17, 1777, including for example: "Oct. 11... we toock a Number of Prisoners to Day... Oct. 13... we toock 15 Prisoners..." [5] Those taken at Bennington, who were "compelled to surrender unconditionally", or prior to Burgoyne's surrender on October 17, 1777, were prisoners of war, and not subject to (or protected by) the Articles of Convention.

Many of those captured before the surrender would be held in towns and villages across Massachusetts, a German officer noting: “Our officers who were really captured are part at Westminster, part at Rutland [Massachusetts]; the captured non-commissioned officers and privates are scattered far and wide throughout the country.” [6] Wasmus' journal details his own march and experiences in captivity, including several meetings with comrades who were part of the Convention Army. Following his capture, Wasmus was marched to Bennington, Vermont, then south to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, before traveling down to Tyringham and east through Springfield, arriving in Brimfield, Massachusetts September 21, 1777.

The movement of prisoners taken during the Saratoga campaign has led to confusion over the route of march of the Convention Army in 1777. Mary K. Stevens, writing in 1897, claimed: "In the latter part of October, 1777, a small party of Convention troops passed through the town [of Norfolk, Connecticut] on their way to Hartford." [7] Stevens apparently reached this conclusion as a result of assuming that any prisoner taken in 1777 must have surrendered at Saratoga, despite quoting from the journal of Connecticut Militiaman Oliver Boardman that he "... was one of the fifty that was called out of the regiment to guard 128 prisoners of war to Hartford." [8] Stevens herself confirms that the prisoners marched to Hartford were not part of the Convention Army, as she later quotes from the Hartford Courant that: "Last Sunday [October 26, 1777] arrived in town 128 prisoners, among whom were several Hessian officers. They were taken at the northward before the capitulations." [9]

The Convention Army's route of march in 1777 is fairly certain. Claims of a third (or fourth) route, a monument along the way in a place they didn't go, and even 18th century documentation of such, are topics for another post.

Next Week: General Burgoyne and Taylor Swift - "Built To Perfection"

Comments

Post a Comment