The Articles of Convention - "Mutually Signed and Exchanged"

On October 14, 1777, Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne Burgoyne, commander of the British expedition to seize the Lake Champlain and Hudson River Valleys, sent a messenger to Major-General Horatio Gates, commander of the opposing American forces, to propose a cease-fire and negotiate an end to the fighting "... to spare the lives of brave men upon honourable terms." Gates replied that Burgoyne's men should surrender, lay down their arms, and march to New England by way of Bennington, Vermont as prisoners of war. Burgoyne responded his men would sooner fight to the death than lay down their arms in their camp, and proposed instead that his army be given free passage to England on the condition that they not serve in North America again. [1]

Gates agreed in principle to Burgoyne's proposal on the 15th, adding that Burgoyne's troops should make ready to begin a march to Boston the following day. Late on the night of the 15th another message reached Gates' headquarters informing him of an error on the part of Burgoyne's officers who had finalized the details of the agreement on his behalf, of whom it was said "... unguardedly called that a treaty of capitulation, which the army means only as a treaty of convention." [2]

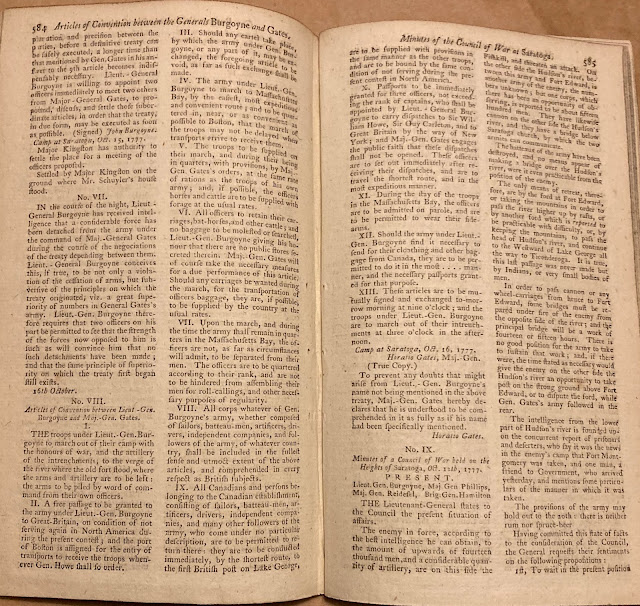

On October 17, outnumbered, surrounded, and low on supplies, Burgoyne's "Expedition From Canada" came to a close under the Articles of Convention that he agreed with General Gates were to be "... mutually signed and exchanged", shown here as published in London in the December 1777 issue of "Gentleman's Magazine". Three days later Burgoyne wrote from Albany, New York, to British Secretary of State for the American Department Lord George Germain asking whether under the circumstances, "... a treaty, which saves the army to the state for the next campaign, was not more than could be expected?" [3] Meanwhile, his officers and men continued their march into captivity.Saratoga was not the first time the Northern Army of the United States handled prisoners. Ensign Thomas Hughes of the British 53rd Regiment of Foot, captured by militia forces in the September 18th raid on Fort Ticonderoga, wrote in his journal that once placed under guard by American who had taken their weapons, "... for two hours we kept silence ... officers and men sent off under two distinct guards..."; and two days later that local militiamen "... who had come out of curiosity to see the Regulars ... were soon driven out by order of the Commanding Officer, who posted two sentinels at our door to prevent further intrusion..." [4]

It's risky to look at history through a modern lens, but difficult not to. My cursory review of several 18th century military treatises found only general guidance on handling prisoners, such as that in 1766 work The Cadet - A Military Treatise by "An Officer" which instructs its readers: "We never insult an Enemy who is disabled from defending himself or hurting us; it is, on the contrary, the received Maxim of every civilized Nation, to treat their Prisoners with Kindness and Humanity..." On a more practical and tactical level, for decades U.S. Army doctrine has directed that prisoners should be handled following the "Five S's", that is soldiers should "search, silence, segregate, speed and safeguard" detainees. For now, let's look at five of the Articles of Convention that relate most to the march, and evaluate each in terms of its appropriateness when handling captured enemy personnel.

Article II provided "A free passage to be granted to the army ... and the port of Boston is assigned for the entry of transports to receive the troops..." Free passage implies that the Convention Army would be moved with speed and kept safe. Gates set the stage for this to happen by assigning Brigadier-General John Glover responsibility for the march, and in the orders he issued for the October 17th surrender, which included that his men: "Let the British army, let Germany, let Europe and all the world know that the troops of the United States are not only great in arms, but that they are as tenacious of the honor and pledged public faith as any of the most polished nations under the sun. The man detected in stealing the smallest articles from any of the prisoners, either in their quarters or upon the march, must expect to be tried by a General Court Martial, and if convicted, suffer death." [5]

Article IV provided that "The army ... march to Massachusetts Bay, by the easiest, most expeditious, and convenient route" Next week we will take a look at the routes taken by the Convention Army. Whether the routes taken were the easiest, most expeditious and convenient may be open to debate, but they were they were the same routes taken by countless Continental and militia troops in the months and weeks leading up to the surrender, and by their predecessors in the decade before, during the French and Indian War, when New England troops were fighting with, not against the British.

Article V provided that "The troops are to be supplied on their march ... with provisions, by General Gates's orders, at the same rate of rations as the troops of his own army..." At the time of surrender Burgoyne's troops had all but exhausted their own rations. Their survival depended on their being fed on the march. Years later Corporal Roger Lamb of the British 9th Regiment of Foot would recall "... having nothing but ... scanty provisions", but on October 18th German troops were satisfied, as one noted "We received provisions from the American stores, and regaled out palates with fresh meat after they had tasted almost nothing but salt pork the whole campaign." [6]

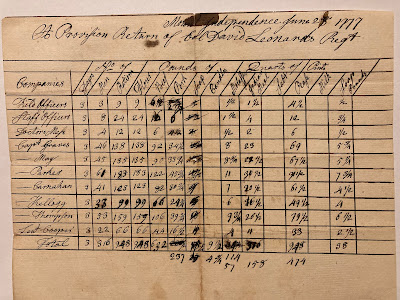

An example of the "rate of rations" provided to American units in the Northern Department in 1777 is this return for for Colonel David Leonard's Hampshire County Massachusetts Militia regiment, dated June 28th, while the regiment was stationed at Mount Independence, Vermont - nine days before its evacuation. Over three days each soldier would have received two pounds of beef, three-quarters of a pound of pork, three pounds of flour, a pint of cornmeal, a pint and a half of dried peas, and about six ounces of molasses. Rations issued to the Convention Army on the march - and their guards - may have been scant at times, but there is nothing to suggest a violation of the agreement. To the contrary, the journal of one Massachusetts soldier, Park Holland, suggests that because the Americans were forced to share what they had with Crown forces, at the start of the march at least, "Some of our soldiers were so hungry they actually picked up and ate some of the hard moldy peas-bread which they threw away on their march up." [7]Article VI provided for "All officers to retain their carriages, batt-horses and other cattle, and no baggage be molested or searched..." This is directly at odds with modern-day doctrine that prisoners be searched for weapons that would be a threat to their captors, and intelligence such as messages or maps, as well as any other contraband. Gates had originally proposed "The Officers and Soldiers may keep the Baggage belonging to them; the Generals of the United State never permit Individuals to be pillaged." The final language of their agreement reflected Burgoyne's counter-proposal intended to protect his officers belongings from being plundered, with the condition that "... the Lt. General [Burgoyne] giving his Honour that there are no Publick Stores secreted therein. Maj General Gates will of course take the necessary measures for security of this Article" - which Gates did through his October 17th orders prohibiting stealing upon pain of death. [8]

Article VII provided that "Upon the march, and during the time the army shall remain in quarters in Massachusetts Bay, the officers are not, as far as circumstances will admit, to be separated from their men. The officers are to be quartered according to rank, and are not to be hindered from assembling their men for roll call,, and other necessary purposes of regularity." This violated the principle of segregation on the march at least, but provided structure to the surrendered forces, and no uprising or mass escape occurred along the way. The expectations it created were evident immediately after the march, when it was proposed (unsuccessfully) at their first meeting in Boston on November 8th that Major-General William Heath, commander of the American Eastern Department and responsible for the quartering of the Convention Army, delegate command authority to Burgoyne.

In summary, much in the terms agreed to by Gates would violate current principles for handling prisoners. In 1777 they set the stage for the conduct of the march, and would be read and commented upon by soldiers and citizens throughout the thirteen United States. A review of reaction to the terms of the Articles of Convention is a topic for later, but Gates would be criticized for both what he agreed to and how he communicated the news. Sufficient to say for now that Burgoyne considered the outcome to be as best as could be expected under his circumstances, and Americans were pleased with their victory.

Later too, we'll look at the implementation of Article I, under which "The troops under Lieutenant-General Burgoyne, [were] to march out of their camp with the honours of war, and ... the arms and artillery are to be left..."

Of note, the Articles as signed did not contain the words "surrender" or "prisoner".

For more on the Convention Army's 1777 march from Saratoga to Boston, see:

1777 March Blog Home Overnight Stopping Points Towns and Villages Along the Way

Comments

Post a Comment